May 18, 2022

Telling Our Story: An Elections Communication Guide

Download the Resources:

Election officials have an extremely important and wonderful story to tell. They oversee and administer one of the best voting systems in the world, one that gives millions of Americans a voice in determining their future and the future of their country.

The need to tell this story is more crucial now than ever before. Public confidence in U.S. elections has declined amid widespread disinformation and confusion about the process.

Pam Fessler, former National Public Radio (NPR) correspondent, talks about the power of good storytelling.

Understanding the Guide

A lack of understanding about the elections process has left a vacuum that can be exploited by those trying to undermine and raise doubts about the system. Without aggressive and creative measures to fill that gap, conspiracy theories will continue to thrive and public confidence will continue to fall, threatening the very foundation of our democracy.

What this means is that election officials need to make communication a top priority.

This guide is intended to help by providing best practices and useful tips in four areas:

-

promoting trust, respect and enthusiasm for our election system and the tens of thousands of people who make it work;

-

countering misinformation;

-

working with the media; and

-

educating voters.

Election officials have a wide range of skills, resources and needs. This guide offers something for everyone. In even the smallest community, strong and consistent communication is needed to assure voters that the system is fair and secure.

There is no silver bullet. Successfully countering the false narratives that have taken hold will require a combination of efforts. The strategies in this guide are interrelated and should be used to reinforce one another. Countering misinformation, for example, involves working closely with the media, educating voters and building public trust.

This is by no means a comprehensive list of the many good communication efforts already in place. Instead, it’s a sampling of practices that could prove helpful in the months and years ahead, and will hopefully inspire fresh ideas. This guide is designed to be a living document – one that can be updated as new challenges and potential solutions emerge.

In the end, the goal is to make sure that voters have the facts they need, and that they hear and believe the stories you need to tell.

The Short List

If you only have time or resources to do two or three things to boost your communication efforts over the next few months, you should:

Establish an engaging social media presence

While most local election offices have websites, a surprising number have no account on Twitter, Facebook or other social media platforms for communicating with the public. Social media is used extensively by those trying to undermine the system by spreading falsehoods, and it’s crucial to reach these audiences with the truth.

Connect with local media and potential allies in the community

It’s important to develop these relationships before a crisis emerges. Invite reporters in now and show them how the process works. Make sure you know what community organizations, businesses and reporters you can call on to help counter misinformation.

Have a crisis communication plan

It’s clear that even the smallest election office can suddenly become the target of a conspiracy theory, often over a minor human error or misunderstanding. Are you ready to respond? Do you have accurate information on hand and in a form that’s easy to disseminate? Do you have a way to get ahead of the story before it gets out of control?

Using the Guide

Table of Contents

- Storytelling

- Promoting Elections and Those Who Run Them

- Drowning Out Bad Information With Truth

- The Media Are Not the Enemy

- Voter Outreach and Education

- Conclusion

- Additional Resources

Storytelling

Peter Bartz-Gallagher, communications director for Minnesota Secretary of State Steve Simon, says, when dealing with election misinformation, “I sometimes think if I could just spend 10 minutes with each voter in Minnesota, we’d have this cleared up.”

Bartz-Gallagher knows that’s impossible, but he has hit upon one of the keys to effective communication. It’s about relating to people on a personal level to help convey your message. Short of sitting down with each voter, the best way to do that is by telling stories — ones that grab a listener’s or reader’s attention and make them receptive to what you are saying. They are stories that show that you, like them, care very much about the integrity of our elections.

This is the theme of this guide. No matter what you are doing — correcting misinformation, educating voters or working with the media — you are trying to tell the story of how our elections work, what protections are in place to ensure they are fair and accurate, and why it matters.

Researchers have found that people are much more likely to accept arguments based on personal narratives than ones based on data and facts. “People are not moved by facts, they’re not moved by statistics, they’re not moved by numbers,” storyteller Donna Washington said on a recent National Conference of State Legislatures podcast. “If you want to reach someone and you have different points of view, stories are the best way to do that.”

During my two decades covering voting and elections for NPR News, the pieces that resonated the most revolved around individuals and the issues they confronted while trying to vote or run an election. My rule of thumb when writing a story was to lead with the first anecdote I told my husband when I came home. If the story grabbed me, it would probably grab the audience too, and still make a larger point.

I’ll never forget a voting rights activist at a rural South Carolina jail, who belted out a spiritual before handing ID cards to newly registered inmates declaring, “Congratulations, Sir. You are a registered voter in the United States of America,” as the other inmates applauded. Or the worker in the Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, election office who routinely combed local obituaries to update the voter rolls, and told me her hardest day was when she had to remove the name of her father. Or the elderly Philadelphia voters, using wheelchairs and walkers, who waited hours at a crowded DMV office to get new IDs so they could vote. These are the stories of American elections.

What does this mean for you? Whenever possible, try to personalize the messages you send. Tell stories about poll workers, election officials and voters, and the incredible things they do to make the process work.

Be yourself, and as direct and sincere as possible. It was standard practice when recording a story at NPR to imagine yourself talking directly to a family member or friend. It was the best way to connect with the listener because your voice reflected passion and sincerity. One correspondent even brought a picture of her husband into the studio so she could tell her story to him.

Be conversational and avoid jargon at all costs. If I could do one thing, it would be to ban the use of the term “logic and accuracy test.” That means nothing to the average voter. Why not tell them you are testing voting equipment to make sure it works? Use plain language whenever you can.

Conducting elections is a serious enterprise, but it can also be fun and rewarding. Your messages should reflect the reason you and so many others continue to do this work despite the many challenges. Even the most routine messages can be engaging.

Kentucky Secretary of State Michael Adams produced a video in 2020 that grabbed my attention because it was a bit playful, but also clear and useful, as he showed voters how to cast an absentee ballot. It could have been boring, but instead, Adams engages the viewer as he walks through the process step-by- step. I love how he points to the envelope, opens his eyes wide and says, “And look! We paid for your postage.” He also notes the instructions on the envelope that “the voter must sign here,” looks right at the camera and says with sincerity, “That’s not a suggestion. The voter must sign here. I want to be able to count your vote!” You believe that he means it.

The last time I checked, the video had 25,000 views on Twitter and more than 4,000 on Facebook. Not bad at all.

Remember, you’re competing with the avalanche of information we’re all exposed to each day. Your message needs to stand out. You are talking to your friends and neighbors about something you believe in and know is important. Polls show that voters trust their local election officials more than they trust those in other communities or states. Use that to your advantage. When you speak, they’re more likely to listen.

Of course, not everyone is comfortable in front of a camera or microphone. Most election administrators like to keep a low profile – the less attention the better. But today, even the slightest mishap can quickly become a national scandal. As trite as it sounds, you need to take control of the “narrative” before it takes control of you. If you can’t do it, find another trusted voice in your office or community who can.

And don’t worry too much about production. In some ways, the more informal the better. Record a video on your iPhone or Facebook Live. The message should be simple: “It’s just me – your local election official – showing you what’s going on and why you should care.”

The most accurate communications about elections are useless if no one is paying attention.

Promoting Elections and Those Who Run Them

A 60-second ad produced by the Virginia Department of Elections opens with the American flag waving in the wind. Backed by gentle, uplifting music, a narrator begins: “The founding story of this great country is also the story of Virginia, because the American ideals we cherish today were born right here.”

The camera soars over construction sites, farms and rolling hills; it zooms in on the faces of the old and the young, families and individuals of multiple races. “Democracy is more than just our way of life. It’s the grand experiment we’ll do everything we can to defend,” the narrator continues.

As the music rises, shots of local election directors and “I voted” stickers and signs fill the screen. The narrator talks about the importance of election integrity and protecting against fraud, while ensuring every vote counts and “every voice is heard … because,” he concludes, “for Virginia, defending democracy through safe and secure elections isn’t just patriotic (pause), it’s personal.”

Virginia’s Democracy Defended ad, which aired on local TV stations in 2021 and appeared earlier online, is a direct appeal to Virginians’ patriotism and civic pride. Former Virginia Elections Commissioner Chris Piper says the goal was to humanize the election process and make clear to voters that elections are run by their friends and neighbors and not by anonymous political operatives with an agenda. “That’s what that commercial is really all about — regular people that are dedicated and passionate about the work that they’re doing,” says Piper. “The other side is tapping into the fear emotion. We need to tap into the patriotic, pride emotion.”

Of all the stories you have to tell, the most important one is this: “Our elections are safe and secure, and run by Americans you can trust.”

It’s about feelings and belief, more than numbers and facts. Those who question the legitimacy of elections refer to what they believe are “facts” about voting discrepancies, but their appeal is largely emotional: “People are trying to steal our elections; we need to take our country back.”

You can counter by appealing to these same emotions – patriotism, desire for freedom and civic pride. You might even find common ground. Many of those who question the voting process believe they too are defending democracy and that if they don’t, they risk losing control of their lives.

You have a compelling response: “Voting is one of the most powerful things an American can do. We should be proud of the system that makes it possible.” You won’t change everyone’s mind, but you’ll change some and inspire others to more proactively support what you do.

Not everyone can afford to produce an ad like Virginia’s, but there are options.

Share resources. Piper’s office spent $150,000 to produce the ad and another $450,000 to buy air time. States or larger jurisdictions with the resources to produce such commercials might consider sharing them, or a template, with smaller election offices. The themes are universal, but the ads can be customized. For example, the election administrators who appear in the Virginia commercial could be replaced by those from other jurisdictions.

Piper thinks such ads can be worthwhile in reshaping the narrative even though it’s difficult to measure their impact. Virginians expressed more satisfaction with the state’s voting process in 2021, but Piper admits that could be due in part to the outcome and the fact that the loser conceded.

Seek free publicity. Local news outlets are always on the lookout for good content and can help get your message out. Reach out and explore the possibilities.

The Shawnee News-Star in Oklahoma, for example, has a “Heroes Of Democracy” series in which it profiles election workers in Pottawatomie County. The county’s election secretary, Patricia Carter, says she suggested the idea to the newspaper in the hope that it would attract more poll workers. One article profiled an 87-year-old woman who is the county’s longest-serving precinct official. Another told the story of a married couple who serve as precinct officials. The husband, a retiree from Tinker Air Force Base, admits he didn’t realize how important it was to vote until he started to work at the polls.

The Guardian newspaper ran a column in 2020 by a first-time poll worker in Alachua County, Florida. The 22-year-old recounted experiences he had in the March primary that will likely resonate with readers — the head clerk telling him that she’d bring chicken soup at 6 a.m and his attempt to help voters keep socially distanced by placing “I Voted” stickers six feet apart on the ground. Readers will also likely remember his conclusion: “I don’t think I’ll ever see voting in the same light, now that I’ve seen all the people who put in countless hours and, in this election, put their health at risk in order to keep a polling location open.”

You can’t control what your poll workers do or write on their own time, but you can encourage them to share their experiences — especially the positive ones. Such personal stories will have much more impact than any official release.

Messaging Suggestions

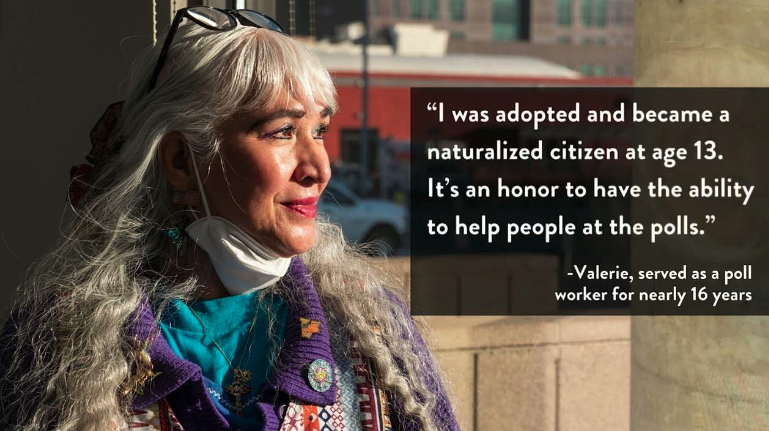

Promote your poll workers. You can also do your own profiles of poll workers – the more personal and engaging the better. People are starved for human stories and there’s a goldmine of material if you know where to look. A photo of an election worker posted online with a quote saying “it’s a rewarding experience” isn’t going to resonate like a short interview with an interesting anecdote or insight.

I was a first-time poll worker in 2018 and two things from that experience stick with me today. I remember how warmly voters greeted and hugged the young man who ran our precinct at a local elementary school. It turns out he had gone to school there and they knew him as a little boy. They were so proud of him and what he was doing! I’ll also never forget how voters and poll workers broke into applause when we learned that a woman with a walker who checked in to vote was 100 years old.

It’s hard to believe that people who worked multiple elections don’t have similar stories to tell. Ask them what they remember most about working on a previous election. What happened that stirred their civic pride? It might take some digging, but will be worth it in the end.

Many jurisdictions are doing more to promote and humanize their poll workers, often as part of an effort to recruit more people to work. Here’s an example from Maricopa County, Arizona:

Here’s an example from McHenry County, Illinois, which produced a video starring three of its election workers. It’s hard to miss that “Love” on one woman’s outfit. Again, the underlying message is that these are your fellow Americans who care that you are able to vote.

Promote yourselves. Don’t be shy. Here’s a 30-second PSA produced by the League of Wisconsin Municipalities, the Wisconsin Towns Association and the Wisconsin Counties Association. The tagline is “We trust our elections, because we trust our clerks.” Three local clerks look straight at the camera, as they speak. Again, no facts. Just stories.

Ellen: “I rely on my neighbors to watch my house when we’re out of town.”

Lisa: “I trust my friends to watch our dog while I’m at work.”

Ellen. “I have faith in my family when I need their help.”

Cindi: “We trust our local elections because our friends, families and neighbors run them.”

How can you not trust these women? The ad’s release also led to favorable coverage in the local media, amplifying the clerks’ message.

This is also an example of the advantage of sharing resources. Most of Wisconsin’s 1,850 local election offices could not afford to produce and distribute such an ad. But the statewide associations could, benefitting even the smallest jurisdiction.

Emphasize your professionalism. Stanford University researchers, in coordination with a state election office, did preliminary research that indicates voters may be reassured by three messages:

-

that elections are run in a bipartisan manner;

-

that the system is transparent; and

-

that election administrators are trained professionals who are on the job all year long.

Former Stanford policy fellow Matt Masterson says many voters think that election administrators “just show up on a Tuesday in November and decide it’s time to roll some voting machines out there and get this thing started.” He says voters’ confidence rose when they were informed that those who run elections prepare and “go through controls and protections just like your auditor does, just like your banker would, in order to secure the process.”

In other words, promote election workers as trustworthy neighbors and friends, but also as trained professionals who are good at their jobs.

Focus your communications. Maricopa County is launching a new media campaign around the theme of “we’re all in this together.” Communications Director Megan Gilbertson says the focus two years ago was on “safety” because of the pandemic. The goal now is to attract more election workers, rebuild public trust and convey the message that “it takes all of us to ensure that we have a secure, transparent and accurate election,” Gilbertson says. That’s especially important in Maricopa, which experienced unusual turmoil and division following the 2020 elections. But unity can be a good theme for others to use as well.

Drowning Out Bad Information With Truth

No one reading this guide needs to be told about the corrosive effects of mis-, dis- and malinformation (MDM). Some of it is spread by foreign actors and anonymous troublemakers, but an increasing amount comes from domestic sources, including politicians and lawmakers. This makes it harder to convince voters that what their local election officials tell them is true.

That’s why it’s more important than ever to establish a level of trust with the public. You don’t want to amplify the falsehoods by repeating them. But they can’t be ignored in the hope they’ll just go away. You need to counter the misinformation by “flooding the zone” with truth. Don’t get discouraged. It will take multiple strategies, and many people and sources repeating the facts — over and over again.

Some tools you can use:

Mythbuster sites. One of the first such sites was set up by the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) in response to a wave of falsehoods about the 2020 election. Since then, many state and local election offices have set up their own rumor control sites, such as this one by the North Carolina State Board of Elections and another by Maricopa County.

Start with the truth. When “busting” myths, CISA recommends describing what’s true first, then citing the myth. This avoids furthering the falsehoods, which are more likely to stick with a reader if listed first.

Here’s an example from the North Carolina site:

Reality: Under state law, voting equipment may not be connected to the internet or use wireless access, limiting the possibility of outside interference. Learn more: Voting Equipment.

Rumor: Voting systems are vulnerable and easy to hack.

The entry includes a link where voters can go to get more information about how the state certifies its voting equipment and what equipment is used in each county.

Don’t respond directly to a misleading post. That can give the MDM more credibility and a longer life. Notice that the entry above describes the rumor in a general way, rather than repeating a specific false post.

Present information clearly and concisely. The shorter and more direct the better. Graphics or images can help. Maricopa County’s mythbuster page presents the “Myth” first, but each one is accompanied by a clear “X” and the word “False” in red type. If you click on the “Myth,” the “Facts” are revealed, marked with a green checkmark. It’s clear what’s true and what isn’t.

Don’t bog the “Facts” section down with too many facts. Voters are less likely to read a lengthy explanation than something short and to the point. You can provide links for those who want more information, as North Carolina did in the example above. Maricopa’s site directs people to both printed material and videos that provide more details about how the county’s voting process works. Some of those videos feature Phil the Ballot, a cartoon character the county uses as a mascot for its voter education efforts.

Be proactive. CISA’s Rumor Control site was reactionary at first. Masterson, who served as the agency’s top election cybersecurity advisor at the time, says CISA made up the process “as we went along,” responding to rumors after they had already gone viral. He says it was like a game of whack-a-mole, knocking down one rumor only to see another pop up. He suggests thinking in advance about what kinds of disinformation you will or won’t address and at what point you’ll respond.

CISA has produced a detailed guide on how to set up a rumor control site.

Try to stay one step ahead. Bad information can appear suddenly and spread rapidly. Some larger election offices have assigned individuals to regularly monitor social media to spot brewing controversies before they get out of hand.

Patrick Gannon, public information director for the North Carolina State Board of Elections, recommends working closely with those who answer your office phones or respond to email. They usually have a good feel for the latest rumors and voters’ questions and concerns. In addition, using a spreadsheet or database to keep track of topics raised in phone calls can help to spot trends and shape your messaging.

The Center for Tech and Civic Life (CTCL) suggests that offices can also set up a Google alert so they know what’s being said about them online. CTCL also offers this checklist for other ways to combat election misinformation and a free, online course on the subject.

Consider partnering with organizations that can do a social media analysis to flag spikes in potentially troublesome posts so you can address them before they become unmanageable.

Assume that if rumors can spread, they will. If disinformation is rampant in one jurisdiction, it’s likely headed your way. You might want to prepare a response, or post something in advance. For example, you can preemptively explain that markers, such as Sharpies, don’t make ballots unreadable (if that’s the case in your jurisdiction, of course)!

Election officials should also assume that any potentially controversial changes they make — such as shutting down polling sites — can lead to rumors and misinformation. It’s best to explain the decisions and the underlying rationale to the public before that happens. Again, try to stay ahead of the story.

Make sure people know the site exists by promoting it on your web page and social media. “No one’s going to go to your rumor control site if they don’t know who you are or what you’re doing,” says Masterson. “It’s important that the public recognize you not just as a bureaucratic entity but as people in your community that they can rely on.”

The National Association of Secretaries of State launched a #TrustedInfo2022 campaign to promote state and local election officials as the best source for accurate election information. Take advantage of that effort.

Gimmicks can also help. The North Carolina State Board of Elections has a catchy title for its weekly posts countering misinformation – Mythbuster Monday. It also has Trivia Tuesday, Fact Friday and Secure Saturday to help answer voters’ questions. This provides regular opportunities to publicize their messages reiterating the facts.

Don’t worry too much if your rumor control site doesn’t attract a lot of clicks. Despite all their efforts, North Carolina’s Patrick Gannon sometimes feels like his office is fighting a losing battle against the flood of misinformation. But the true value of such sites is that they’re there when you need them, and can be used by others to help spread your message.

Maricopa County’s Gilbertson says she directed reporters to the county’s “Just the Facts” website to help answer their questions about the latest allegations and conspiracy theories. These media outlets then reported that information to a wider audience. Gilbertson says it was also easier to answer hundreds of public comments and questions the county received online by responding with links to the relevant section of its “Just the Facts” page.

Neal Kelley, former registrar of voters for Orange County, California, says his office’s phone operators were also able to email links to their mythbuster page in response to questions about something a voter “saw on the internet.”

“That has resonated more with voters than [us] just hoping they see the information on our website,” Kelley says. He also was able to refer to the mythbuster page when meeting with community groups and concerned voters.

Direct engagement. Another way to counter misinformation is to meet in person with those who believe it. Such meetings are often frustrating and time consuming but they allow officials to answer specific questions and use their influence as a “trusted source.”

When they work, these in-person meetings can produce great dividends.

A case in point. Carly Koppes, clerk and recorder for Weld County, Colorado, spent four hours with one voter who bought into many of the latest conspiracy theories. Koppes started by explaining the history of state election practices and the day-to-day operations of her office. She then gave him a tour, provided relevant documents and answered his questions. The voter is now one of her staunchest defenders, pushing back against critics on social media, calling into radio talk shows and attending gatherings of election deniers to counter their claims. “It has been really nice to have others, who aren’t me, going out there and saying, ‘No, actually Carly is telling the truth, you guys, and have you spoken to her,’ and kind of calling people out,” Koppes says.

She says such one-on-one meetings can have a valuable ripple effect. “I’m affecting that person, but they know ten people and they’ll share their experience with ten people … and then those ten people know another ten people and that’s a hundred people I’m not going to have to talk to, hopefully,” she says. Koppes notes that it’s similar to how disinformation is spread, adding, “I’m not going to allow these other people to be the only ones with the microphone.”

Some additional tips:

Figure out who to meet with. You can’t meet with everyone, so focus on those who have the most influence with others who believe the falsehoods. Neal Kelley of Orange County says he often met with the leaders of fringe groups questioning the integrity of the elections. He thinks he was able to “chip away” at their concerns by showing them how the process works and countering their arguments with facts. If he convinced them, he says, these individuals eventually “spread good will for us” by sharing what they learned with their supporters.

“It didn’t completely change the hearts and minds of true believers, but what it did do was soften the blow,” Kelley says.

Chris Piper says his Virginia office routinely looked at who was filing public records requests – a popular tool for those questioning the voting process – and reached out to meet with them in person. He says that allowed him to answer their questions directly “rather than them coming to their own conclusions based on conjecture and assumptions.”

Expect only partial success. You need to be realistic about such meetings. Wesley Wilcox, supervisor of elections in Marion County, Florida, says there are some people whose minds will never change no matter what. “You have to recognize who those people are and focus on those who are reasonable and you can talk common sense to.” He, like Koppes and Kelley, says it’s worthwhile even if he can only reach one person at a time. “Just like there’s a constant drumbeat of malformation, I’ve got to do the constant drumbeat of truthful information,” Wilcox says.

Focus the discussion. To keep such discussions from getting out of control, Wilcox recommends making sure those you meet with have specific questions they want answered. Wilcox tells his guests right from the start that they have to let him completely respond to one question before moving on to the next. Otherwise, such meetings can become counterproductive free-for-alls.

Be prepared. Kelley compiled fact sheets and reports on his operations in advance. He was then able to refer his visitors to them in response to their questions. He says a California Institute of Technology analysis of his county’s election system was especially helpful because it came from an independent group and therefore carried more weight than anything he might have said. Kelley suggests that smaller jurisdictions might want to ask a local college, university or other reputable third party to do a similar assessment of their offices to help boost public confidence.

Al Schmidt, a former commissioner on the board that oversees Philadelphia’s elections, says it’s crucial to have your facts straight when communicating with those who are questioning the election system. “You have to fight them back with facts, and you can’t be wrong when you do. Your best asset is your credibility,” he says. Schmidt admits he had a big staff to run down specific allegations — such as “dead people” voting — to make sure they were not true before he responded. Smaller offices, without those resources, can try to anticipate questions in advance so they have the answers on hand (another reason for a mythbuster site).

All jurisdictions should have written standard operating procedures, so the information is available when questions arise. Written procedures provide a foundation to create talking points and rumor control sites. They also help ensure that what you are saying is reflected in the actual work being performed, allowing you to confidently state the facts and refute false claims.

Appeal to voters directly. The Colorado Department of State used a broad marketing campaign to counter the spread of false information and to promote itself as a “trusted” source in 2020.

The paid ads, which ran on social media and the digital versions of local newspapers, were designed to resonate specifically with Coloradans. They featured cartoon graphics with clearly false but snappy statements such as, “Climbing Longs Peak is easy,” followed by “Opinions are fun. Facts are better” and a link to the state’s election website “for facts.”

Colorado Elections Director Judd Choate says his office encouraged nonprofit groups to repost the ads online to help amplify the messages for free. The state also bought ads on Google to appear at the top of the page if someone used search terms such as “election integrity” or “fraud.”

Build coalitions. You are not alone. You have many allies in your community, state and around the country who can help you communicate with voters. A local official posting information on the office website to counter a misleading rumor is one thing. Having a coalition of diverse, influential voices repeating that same message is another.

Here are a few suggestions:

Join forces with other election officials. Disturbed by persistent claims of voting irregularities, Florida’s 67 county supervisors issued two powerful statements in 2021. In the first, the supervisors assured voters they “can be confident in the professionals they elected to administer our elections, and the protections that ensure every ballot is counted accurately and only eligible Floridians are on the voter rolls.” In the second, directed at state politicians and lawmakers, the supervisors noted how disinformation was undermining Americans’ trust in the electoral process and asked “candidates and elected officials to tone down the rhetoric and stand up for our democracy.”

The statements were noteworthy because they were released with the unanimous backing of a bipartisan group of election professionals. Wesley Wilcox was president of the supervisors’ association at the time. He thinks the fact that he is a Republican gave the statements additional clout because most false claims about the 2020 election came from his side of the aisle.

Wilcox says the releases also encouraged the state’s election supervisors to become more proactive in defending the system. “We recognized that no one else is going to stand up for the professionalism and the accuracy and security and honesty in our system, if we don’t stand up and set the record straight,” he says.

A similar bipartisan statement was released in Kentucky in response to unsubstantiated fraud allegations from a group calling itself the “Restore Election Integrity Tour.” The letter was signed by the Kentucky secretary of state, the State Board of Elections and the Kentucky County Clerk’s Association. “We are the real people — the citizens who love Kentucky sufficiently to work long hours, even in the face of occasional physical threats, to run these elections — and we have had enough. We encourage Kentuckians to accept election information only from legitimate sources,” the letter said.

A bipartisan group of Colorado county clerks also held a news conference in April 2022 to show their solidarity in countering unfounded allegations of fraud. The news conference was noteworthy because it was held before a planned rally by election deniers, rather than afterward. The clerks were able to get ahead of the story and set the tone for media coverage.

Unite with other trusted voices in the community. Even the smallest election office is part of a larger community of civic groups, churches, schools, businesses and nonprofits. Leaders of these groups – including clergy members, sports coaches and local celebrities – can spread your message to a larger audience. If you aren’t doing so already, work with them to help educate and reassure voters that the process is secure.

In Minnesota, Bartz-Gallagher says he relies heavily on outside groups to get their message out. He believes most of his office’s direct communications can have limited reach because it’s essentially “preaching to the choir, the kind of people who probably already know that misinformation and disinformation are a problem.” But he says the benefit of preaching to the choir is that “the choir is influential in their own spheres” and can help spread the word.

State legislators are also potential allies. The National Conference of State Legislatures has advised lawmakers on how they can help counter election disinformation. The first suggestion it offers: “Do Your Homework. One of the best ways to do that is to tour your local elections office(s). You’ll learn from the experts how your state’s elections are managed and get the information you need to respond to constituents’ questions. Plus, you’ll strengthen your relationship with your local election officials—and that can pay off down the road when crafting election legislation.” Seems like an offer you can’t refuse!

The Election Official Legal Defense Network (led by attorneys Ben Ginsberg and Bob Bauer, along with the Center for Election Innovation and Research) is also working on ways to help build coalitions of local business, civic and religious leaders to support election officials. The program is in the pilot stage, but you can contact them for more information.

Back up your colleagues. An attack on one election office can undermine confidence in all the others. While local election officials are uncomfortable vouching for what happens in other jurisdictions, there are some things you can say with confidence. You know what protections are in place in other counties in your state and also that most election officials are hardworking professionals committed to running honest and fair elections. Say that. You also know that allegations of fraud and irregularities are usually false and involve misunderstandings about how the process works. Say that too. Then direct people to trusted sources in those areas where they have concerns.

Work with the media. There’s much more below, but the media can be a valuable ally in setting the record straight. Not only do many outlets have fact- checking columns that are helpful in countering election myths, some officials have been able to get op-eds and regular columns published in local newspapers. A “mythbuster” column by Kaiti Lenhart, supervisor of elections in Flagler County, Florida, was reprinted in the Daytona Beach News-Journal.

The Media Are Not the Enemy

In the war against disinformation, the media – for the most part – are your friends. Mainstream journalists are as interested in communicating the truth as you are. You should take advantage of that. Turning to the media for help can be especially valuable for smaller jurisdictions that lack the resources or personnel to do paid advertising or their own publicity. But it takes advance planning:

Identify which local reporters cover election and voting issues. Do it now. It’s crucial to make these connections before a controversy emerges and you suddenly have to respond to a rumor or falsehood. It takes time to develop the kind of relationship you need with a reporter or media outlet to get the best and most accurate coverage. If possible, connect with reporters on the state and national level too, or make sure your state election office has done so and will help if a local story starts to blow up.

Small media outlets are unlikely to have a reporter assigned specifically to elections, but almost all have someone covering local government. Contact them to find out who is the right person to talk to. Or contact the editor or newsroom manager. Remember to include all your influential local media, whether it’s TV, print, radio, Spanish-language outlets or a popular podcast. If you’re a small office, you might seek advice from your local government’s public information officer on who to contact and how.

Get acquainted. Once you’ve identified reporters who will likely be covering voting issues, give them a call. Get to know them and let them get to know you. Peter Bartz-Gallagher of Minnesota says he likes to do this informally over coffee. Exchange contact information and let these reporters know you’re available to answer their questions or that you can connect them with someone who can. It’s all about trust on both sides. Reporters need to know you’ll be frank with them. You need to know the reporters who cover you will be accurate and fair.

Megan Gilbertson of Maricopa County says developing this relationship in advance is key if you want reporters to touch base with you before reporting on allegations about fraud and irregularities. She says her office reached out to every print outlet and broadcast station in the area in 2019 and 2020 to explain who they were and how they operated: “So when we got to the crisis situation, one, they had that background and two, they knew to call us to get the full picture about what was happening.”

If you have a good working relationship with the media, reporters are also more likely to spike (or kill) a story they’re working on if you can explain that there’s really nothing to report. Jessica Huseman, who covered voting for ProPublica and is now editorial director for the nonprofit news outlet Votebeat, recalls being alerted by voting rights advocates that a state had purged hundreds of thousands of Democrats from its rolls. It had the potential to be an explosive story. Huseman contacted state election officials, whom she had worked with before, and decided not to do the story after they explained that what appeared to be a “purge” was the result of a temporary, technical issue. Huseman says it was especially important that state officials put her in touch with an elections office IT expert who could answer all her questions and explain what was going on.

Educate reporters about the process. Most reporters have never covered election administration before. In the same way you need to educate the public, you need to educate reporters about how the process works so they can accurately report on it.

Invite them in to see your operation firsthand. With the exception of voters’ personal information, you have nothing to hide. Let them take or attend poll worker training classes. Let them see how you test and secure voting equipment, and how you count and safeguard the ballots. If you do “red teaming” to identify vulnerabilities in the system, consider allowing reporters to participate, even if it needs to be done “off the record.” Matt Masterson notes, for example, that if reporters can see for themselves that equipment is not connected to the internet, they’ll know how to deal with allegations that it is.

Neal Kelley of Orange County highly recommends opening the doors as wide as possible. Every election cycle, he offered reporters the chance to come in and go wherever they wanted to see how his office functioned. He even allowed reporters to travel around the county with support personnel, which Kelley says shocked some of his colleagues. “I get the same question: ‘You let reporters drive around with your field personnel?’ And I say, ‘Absolutely! We have to be transparent.’ They’re going to see the problems, but at the same time they’re going to see the good,” he says.

That’s been my experience too. Timothy Benyo, chief elections clerk in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, gave me free access to his office one day before the 2020 election. I spent hours talking to workers and volunteers, watching as they did their jobs. This was all without Benyo standing over my shoulder, so I didn’t have to wonder if the person I spoke to was being honest or trying to please the boss! It was an eye-opener to see the incredible volume of mail the office had to sort through each day and the nonstop phone calls from confused voters. It would have been one thing for Benyo to tell me how overwhelmed they were because of last-minute voting changes due to the pandemic. It was another for me to see it firsthand for a story that aired on NPR and was heard by millions of listeners.

You can also hold background briefings with reporters right before an election to go over how the process is expected to unfold and to answer questions about potential concerns. CISA held such a briefing for national reporters in 2020 with representatives of multiple intelligence agencies. They provided the latest information on potential foreign and domestic interference so reporters had a better idea of what to look out for on Election Day.

Pitch or help craft stories. One way to establish a good relationship with the media and to amplify your message is to propose specific stories before an election about how the process works and what you are doing to prepare. Invite a local reporter or TV crew to do a story about poll worker training or testing equipment, for example. This kind of free publicity can be especially helpful for smaller jurisdictions. You not only get to inform your voters, but can build a relationship with the local reporter. “Not every county has the ability to make educational videos, but you know who does have the ability to make videos like that? The local news,” says Huseman.

A Utah broadcaster produced this two-part series (part 1 and part 2) after election officials in Weber County, Utah, walked him through the process.

In Janesville, Wisconsin, Clerk-Treasurer Lori Stottler showed a local reporter how her office tests the accuracy of its voting machines. The broadcast not only described how it was done, but informed viewers that they could see the testing for themselves at an upcoming open house. Stottler says the story came about after the city posted something on social media advertising the open houses. This caught the eye of the reporter, who called for an interview. His story led to two more on other local TV stations and an online news site. “I’ll take all the free media I can get,” Stottler says.

One caveat: Stottler was disturbed that one reporter got some of the information wrong and misquoted her. She plans to be more careful working with that reporter in the future, only giving written responses so she has a record of what she said.

That’s good advice. It might not be in your best interest to speak with a reporter who has historically not treated your office with fairness. Instead, request that the reporter send their questions via email. Responding in email allows you to (1) carefully write your message and (2) avoid instances of a reporter – well-meaning or otherwise – deriving an alternate meaning from what you intended to say.

One suggestion: In cases like the one Stottler encountered, always make sure the reporter who got the information wrong knows what he or she got wrong. You should try to work with them — even if it has to be on background — to make sure the next story is correct. Most reporters want to be accurate, but no one is perfect. Don’t cut them off unless you know they are intentionally misreporting the story. You want your side of the story told, or else others will fill the gap with more misinformation.

Personalize your message. Besides the mythbuster column mentioned above, Flagler County Supervisor of Elections Kaiti Lenhart had another story about her work published in the Palm Coast Observer. The article was an edited version of an interview the executive editor did with her for the newspaper’s podcast. What’s nice about the interview is that editor Brian McMillan asked Lenhart several questions about her home life (including the fact that she has a 1,200-square-foot home garden), establishing her as a “regular person” before turning to what she did to help secure local elections. Lenhart believes the interview had positive results. She saw an increase in people going to her office website’s security page and several voters reached out to her in person. McMillan says it was his idea to interview Lenhart because of ongoing public interest in election security.

Make the experts available. Spokespeople for election offices need to help, not hinder, access to information. Journalist Huseman says it’s crucial that reporters be able to talk to the person who can actually answer their questions, who is not always the media contact or election director. Sometimes it might be the IT expert (as in Huseman’s example above) or some other specialist in the office who has the information, even if you don’t want that person to be quoted directly. The most important thing is that journalists understand what’s going on so they can put whatever they’re reporting about in the proper context and explain it clearly to the public. A short “sound bite” is seldom helpful.

“On background” and “off the record.” Know the difference. “On background” means a reporter can use the information and attribute it to an unnamed source such as “a local election official” or “someone familiar” with the topic. “Off the record” means the information cannot be used in a story, but is provided to help the reporter put what they’re reporting about in context or give them guidance on where to do additional reporting. While reporters generally prefer most things to be on the record, they understand that it is not always possible. Sometimes election officials have to avoid being quoted on sensitive topics, especially in today’s highly politicized climate. This is why those relationships with the media are so important, so you know who you can trust and that they can trust you.

Huseman has created a handy flow chart (below) to help you decide when to go on background or off the record. It doesn’t fit every situation, but gives some idea what to consider when making your decision.

Votebeat journalist Jessica Huseman created a flow chart to help officials determine when to speak on the record, on background or off the record.

Clarify in advance if you’re saying something on background or off the record. Otherwise, journalists will assume anything you say is on the record.

Use these techniques sparingly. You’re a public official and information attributed to you is much more credible than that coming from an anonymous source. If you’re trying to win the public’s confidence, it’s better for them to know where the information is coming from.

Other options. Huseman notes that if you want to convey information that you don’t want attributed to you, there are other things to do besides going off the record. One is to suggest to a reporter that they file a public records request for certain documents. You can also direct them to other individuals or officials who can verify the information you want to share.

Be honest and transparent. If there’s a problem, say so. If you don’t yet have a good explanation for what’s causing the problem, say that too. It might be embarrassing or uncomfortable, but if you’re not transparent, reporters and the public will think something nefarious is going on, which further undermines public trust. You should also make clear what, if anything, you’re doing to address the problem. If you’re honest and transparent, people are more likely to cut you some slack.

For example, Maricopa County’s detailed response to allegations made in a so-called “audit” of its election results acknowledged that one batch of 50 ballots might have inadvertently been counted twice. That admission gave more credence to the county’s rebuttal of all the other claims in the report.

Return reporters’ calls – at least most of them. A recent news story about an election commission’s decision to shut down almost 20 percent of an Arkansas county’s polling sites was dominated by critics accusing the county of voter suppression. The reporter said she reached out to the commission for comment but “didn’t hear back.”

Too many stories about elections include similar lines or a “no comment” from election officials. Sometimes it’s not your fault. The reporter might be on a tight deadline and not give you much time to respond. If you can, at least answer the phone to tell the reporter that you are not able to comment and why. Ignoring the call won’t make the issue go away and cedes control of the debate to critics. Better yet, get ahead of stories like this by approaching reporters in advance with your side of the story.

One caveat: On rare occasions, you might encounter a reporter who is not acting in good faith, or someone who calls themself a “journalist” but is actually an activist working for a fake “news” site. Unfortunately, this trend is growing, especially when it comes to covering elections. If an unfamiliar reporter calls you up, you can vet them before responding. Search online to see their previous work. If you have concerns, feel free to ask the individual more about the outlet they work for, who their audience is and the focus of their story. If it becomes clear that they have no intention of presenting the facts, you can politely decline to engage or respond to their questions in writing.

Write it yourself. Many news outlets, especially smaller ones, are always looking for good content to fill space or air time — especially if it’s free. Reach out and offer to write an op-ed or column.

That’s what Paddy McGuire, auditor for Mason County, Washington, did. He asked the editor of the local weekly newspaper, the Shelton-Mason County Journal, out for coffee and proposed writing a regular column leading up to the 2020 elections. McGuire knew that in his small, rural county the newspaper was a major source of information for voters. He was new to the job and saw the column as “a way to establish myself as a trusted source of information from the beginning, so when things got crazy towards November, people might be more receptive to listening to me and our office because I’d been talking to them for a year.”

The editor liked the idea and that was the beginning of McGuire’s biweekly “Elections Matter” column. He wrote about everything from voting by mail to dispelling rumors about invalidated mail-in ballots. He tried to write the column in a way that would appeal to a wider audience. He says he avoided election jargon and would think about one of his neighbors and what words he’d use if they were talking in person (just like the NPR reporter who read her scripts to a picture of her husband). A typical column began like this: “Election officials plan and prepare for things to go wrong. We think about the weather, things like blizzards and flooding. We think natural disasters, earthquakes, and since we are in Washington, volcanoes.” Direct, clear and personal. The Center for Tech and Civic Life has more of McGuire’s story, with links to some of his other columns.

Get help. If you don’t feel comfortable writing your own column or op-ed, try what Virginia’s former elections commissioner Piper did. His office contracted with a former reporter to work with county registrars to help them write op-eds for local newspapers and to do radio spots. “These local offices, they’re just not resourced enough,” Piper explains. Here’s an example of one of the local radio spots, produced with the state’s help.

Crisis communications. When a major election incident occurs, it’s crucial to communicate with the media and the public as quickly as possible to prevent rumors and misinformation from taking hold. One of the best examples in 2020 was in Georgia, where officials faced a barrage of questions and attacks about its voting process. The secretary of state’s office held regular, televised briefings once – sometimes even twice – a day.

Stephen Fowler, who covered the story for Georgia Public Broadcasting, likened it to what government officials do in the midst of a natural disaster. He says it was reassuring to have a familiar face in front of the cameras each day and for reporters to have access to someone who tried to answer all of their questions in an understandable way and “in real human terms.” Fowler notes that the person answering the questions changed depending on the topic, and that these officials made clear what they did and did not know.

Elections officials in other countries often set up media centers in the days before and after an election to provide regular briefings. That might not be possible for smaller jurisdictions, but it is something for states or larger election offices to consider if they’re not doing so already.

Don’t get overwhelmed. Al Schmidt, whose Philadelphia office was also a major target of disinformation and malicious attacks in 2020, says he was inundated with media requests. To prevent all of his time from being consumed by interviews, he decided to be selective. Schmidt picked a couple of major outlets he trusted — The Philadelphia Inquirer and CNN — for most of his interviews. He found that what he said on those two outlets was usually picked up by other reporters covering the story, leaving him more time to oversee the election.

Schmidt says he also found Twitter an effective way to communicate quickly with the media in response to breaking news, such as President Trump’s demand in the early morning hours of Nov. 4, 2020, that Philadelphia stop counting its ballots.

Get ahead of the story. Officials in Lincoln County, Georgia, might have had good logistical reasons to consider shutting all but one of their polling sites last year. But they quickly found themselves on the defensive against allegations of voter suppression and the focus of national news coverage. GPB’s Stephen Fowler says one problem is that the county failed to make clear in advance why it wanted to shut down the sites and what steps it was taking to help affected voters. Fowler did a story that included more details about the county’s motives, but the damage was done and the county eventually shelved its plan.

“I’ve found that the more preemptive communication that happens, the less retroactive filling in gaps people have to do, or that bad actors can exploit,” Fowler says.

Voter Outreach and Education

Those who attack the voting process can take advantage of the public’s lack of knowledge about how the system works to generate uncertainty and fear.

Consider the confusion in 2020 over the counting of mail-in ballots. Election officials and the media warned repeatedly that it could take days to count these votes — and that it could change which candidate was in the lead. Still, some voters and candidates expressed outrage that tens of thousands of ballots were, they claimed, “mysteriously found” after the polls closed. This was used by some candidates as “evidence” of a stolen election.

Conspiracy theorists also pointed to another routine practice as evidence of fraud: election workers replicating ballots to replace those that are ripped or can not otherwise be counted by voting equipment.

Simply put, explaining how the process works can offset efforts to undermine trust. A survey by the Colorado secretary of state’s office found that public confidence rose when voters learned about the specific steps taken to protect election integrity, such as the fact that the state “tests every machine used in the election to ensure they are secure.” Or that “teams of election judges made up of Democrats and Republicans conduct signature verification on each mail-in ballot.”

Many election offices already have extensive voter education efforts, but more can be done. The U.S. Election Assistance Commission has released a new multi-media toolkit to help jurisdictions of all sizes communicate with the public. It includes customizable templates to help produce documents, posters, handouts and PowerPoint presentations to explain how the election process works using clear and consistent language.

It’s also important to manage expectations about elections. The more people know in advance about what to expect and when, the less confused and more confident they’ll be. These communications should be aimed at all election stakeholders – from voters to political campaigns to community groups.

A few tips:

Keep your messages simple. Political scientists Mara Suttmann-Lea and Thessalia Merivaki have studied the impact of social media posts by election officials. Their research finds that voters respond more positively to messages that focus on a single topic, rather than those that cover multiple issues. “Attention, space, time — they’re all limited,” says Suttmann-Lea, an assistant professor at Connecticut College. “So if there are certain aspects of the election process that are really important to you to prioritize, then you have to prioritize them.”

Suttmann-Lea says it’s also important that such messages make up a larger share of your online messages. She and Merivaki studied posts by election officials in North Carolina about mail voting and found that voters were more likely to have their mail ballots accepted if they lived in counties that devoted a higher percentage of social media messages to describing the process. Voters were more likely to have their mail ballots rejected if they lived in counties that devoted a smaller share of their posts to that topic.

Merivaki, who is an assistant professor at Mississippi State University, provided this example of a simple, straight-forward message from the Buncombe County elections office on how to return an absentee ballot in person.

She compared that to a post from another county that covered a long list of topics, such as the hours for voting and the location of early voting sites. It also included links to help voters find their registrations, sample ballots, voting location, how to vote by mail, how to check the status of their absentee ballot and information about military and overseas voting. All useful information, but only if people bothered to read it.

Keep it short. Several election offices have started to post brief (about 1-3 minutes each) videos online to help educate voters. People are more likely to access these bite-sized posts than to read lengthy online descriptions.

The Idaho secretary of state’s office has produced 40 short, animated videos, each detailing a different step of the election process from registration to certification.

Chief Deputy Secretary of State Chad Houck says the videos are designed to boost voters’ confidence by helping set realistic expectations about how elections work. “If they’re not satisfied with their voting experience, it tends to correlate in a lower confidence in the election process,” Houck says. “You’ve got to set the right expectation.”

Houck adds that local election offices in Idaho can now respond to voters’ questions with a consistent answer by linking them to the relevant video. The series cost about $50,000 to produce (not counting his and other staffers’ time). The videos were released one at a time over the course of a year, giving the state plenty of opportunity to promote the education campaign.

Oregon is also using short PSAs to stay ahead of potential misinformation. “We are committed to reaching Oregon voters early and often, so the first thing they hear about Oregon elections is the truth,” Secretary of State Shemia Fagan told one local TV station. The first ad is focused on how to register and vote in the state’s closed primaries.

Election Supervisor Craig Latimer of Hillsborough County, Florida, has also begun what he calls a “long series of short videos about voting.”

Make it fun and upbeat. Voting is a serious responsibility, but it can also be fun. Try to be a little lighthearted in your messaging, so it stands out against all the negative information and encourages voters to participate.

Oregon Secretary of State Fagan tweeted this TikTok clip in which she encourages voters to update their registrations.

She does so by challenging viewers to see whether it’s faster for her to learn her son’s bottle-flipping trick or for a voter to update their registration. She wins the contest, but it’s close and the point is made – both are quick to do. Fagan makes another point too. She’s a fun mom who also runs elections. This is one of several clips the office has put on TikTok encouraging voters to register.

A 2014 commercial by then Mississippi Secretary of State Delbert Hosemann — where he follows a voter out of a meeting to a park bench to a restaurant to his fishing boat as he lists the many ways a voter can get a free ID — won a national advertising award. More importantly, it made a serious point in a light- hearted way: Mississippi voters have many options.

In Chaffee County, Colorado, Clerk and Recorder Lori Mitchell used a series of tweets to show some of the more creative ways voters do “drive-through” voting.

And, of course, there are cats and dogs. The Athens County, Ohio, board of elections office has gotten a lot of mileage out of its resident cat, Pumpkin, whose image has been used to remind people to vote. This tweet showing Pumpkin sitting in the office window received 32,000 likes!

Get more social. Mara Suttmann-Lea found that local election offices have a surprisingly limited social media presence, despite the examples above. Most of the 6,000 offices she surveyed in 2020 had websites, but only 34 percent had an active Facebook page, 8 percent used Twitter and 2 percent used Instagram.

On the other hand, those spreading election conspiracy theories are often part of a massive social media network and can have hundreds of thousands of followers. Suttmann-Lea says local election officials often ask if social media is worth their time. “Yes, having a social media presence is important and also how you use it is important,” she says.

Digital marketing expert Steve Wanczyk founded a nonprofit group, called Protect Our Election, to help elections officials counter disinformation and boost their social media presence.

Wanczyk says one way to increase engagement is to actively ask people to follow you or to share your posts. “There’s no shame in asking for followers. That’s how people grow accounts,” he says.

Wanczyk has some other tips:

Establish an account. Create accounts on Twitter and Facebook using a generic office email (i.e., not someone’s personal email) and with a generic account name (i.e., not the current office holder’s name). Please note that there are First Amendment implications in managing an official account representing a governmental entity.

Personality goes a long way. You may be using a generic office account, but that doesn’t mean you can’t inject a little of your personality into the content. Be yourself, be authentic, and bring a little creativity to the platform.

Know your community. Take advantage of social media analysis services (like Protect Our Election’s pro bono offering) to ensure you are on top of what your constituents are talking about on social platforms. Weekly reports can help you sort through the noise and zero in on the topics most in need of a proactive response.

Grow your followers. It’s not enough to simply have an account, if you have a minimal number of followers. Take steps to grow your follower base by stressing the importance of local government and asking folks to do their part to strengthen local government by spreading trusted info.

Invite responses. Encourage your followers to engage with the account by asking for personal stories, experiences related to voting… even complete non sequiturs can be a perfectly appropriate way to invite comments.

Comment yourself. Boost your office account’s visibility by following other locally-relevant accounts and dropping an occasional comment on their posts. This allows you to get your account in front of more users, while also building that deeper connection with constituents who might be following other local sources.

Post images and videos when possible. Research shows that multimedia content generates high engagement rates, and sticks with users.

Optimize your workflow. Use tools like TweetDeck or Hootsuite to manage your social accounts. These tools allow you to pre-produce and schedule posts so that you can manage your time more efficiently. You can do a week’s worth of social posting in one 30 minute block of time.

Several jurisdictions have developed social media policies to help manage use and ensure compliance with the law. An example comes from the Portage County, Ohio, Board of Elections.

The Center for Tech and Civic Life offers a specific “Social Media for Voter Engagement” course. The participant guide includes best practices and design recommendations.

Open your doors. Many election offices have been doing this for years. But they’ve often had trouble interesting members of the public to attend a tour or observe operations such as “logic and accuracy” tests (again, that phrase!). It’s worth making an extra effort now before things become too hectic. Nothing works better than showing people what you do in person.

The election office in Davis County, Utah, has been very effective at promoting its open houses by emphasizing that “no question is off limits.” A TV news story covered one of the sessions, promoting additional times when voters could come in and see for themselves.

What’s striking is how positive the coverage is. The reporter interviews County Clerk/Auditor Curtis Koch and reports that “he [Koch] knows in this climate there’s no substitute for being transparent.” The message at the bottom of the screen reads: “Election Security Meeting: Davis county clerk hopes to build confidence in the process.” While only about a dozen people attended this open house in person, many more presumably saw the report on TV.

A similar story appeared two weeks later in the local newspaper, which addressed common myths about voting. Chief Deputy Clerk/Auditor Brian McKenzie was quoted saying that anyone with questions “can contact me at any time.” His office phone number was listed at the end of the article.

McKenzie believes the open houses have shifted the thinking of some skeptical voters. “We spend as much time as they need explaining the process,” he says. The county has since added an option for people to attend the meetings virtually.

Enlist the community. Again, you’re not alone. Civic groups and other local groups can help you educate voters. Rhode Island’s secretary of state distributed a communications guide to community leaders in 2021, with infographics and posters to use in public outreach. The guide included sample social media posts and emails, as well as links to videos explaining the process. State officials say they saw an uptick in the use of images from the guide and toolkit on social media sites and increased traffic on their website – although they did not know how much of the latter was due to the guide. The state plans to make a similar push this year, reaching out to local organizations and small businesses to help educate voters.

The Center for Civic Design’s Elections 360 effort is aimed at developing best practices to help election offices and community groups work together and to improve voter confidence. It also has useful guides on communicating with voters and designing effective voter education materials.

Conclusion

We’re all inundated with information. So when communicating, think about your own experience. Which of the many messages that you received over the past week do you remember most? Most likely it was one that came from a family or friend, or struck a nerve because it was new, different and personal. Whatever it was, if it worked for you, it will likely work for others.

Remember:

-

You have a wonderful story to tell.

-

Tell it. (Or get someone to tell it for you!)

Additional Resources

Toolkit for Communicating Election and Post-Election Processes (U.S. Election Assistance Commission)

Guide on Using Video to Tell a Story (The Elections Group)

Guide to Setting Up a Rumor Control Page (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency)

Checklist for Combatting Election Misinformation (Center for Tech and Civic Life)

Series on Communicating Trusted Election Information (Center for Tech and Civic Life)

30 Ways Election Officials Can Boost Public Trust (Center for Tech and Civic Life)

#TrustedInfo2022 Campaign (National Association of Secretaries of State)

Elections 360 Project on Connecting Community Groups and Election Offices (Center for Civic Design)

Guide on Choosing How to Communicate with Voters (Center for Civic Design)

Mis/Disinformation and Cyber Incident Communications Response Guide (Harvard Belfer Center)